Project 888

Over Indy's 12+ years of consecutive service in the United States Naval Fleet, there were a

total of ten U.S. Navy Captains who served in the role of Commanding Officer (CO) aboard

USS Indianapolis (CA-35).

Over Indy's 12+ years of consecutive service in the United States Naval Fleet, there were a

total of ten U.S. Navy Captains who served in the role of Commanding Officer (CO) aboard

USS Indianapolis (CA-35).

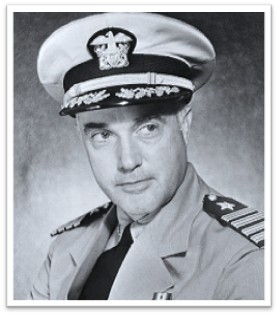

Captain Charles B. McVay, III was one of those men and he served as Indy's CO (aka Skipper) during the last two campaigns in which Indy CA-35 earned her 9th and 10th Battle Stars.

Captain McVay would ultimately serve as the ship's last CO.

Captain McVay retained his command of the ship throughout the Mare Island overhaul and repair.

On 12 July 1945 (just over 2 months after arriving at Mare Island), Captain McVay was informed that Indy had been selected for a Special Assignment.

He received orders that Indy was being scheduled to leave Mare Island on 16 July 1945

and would be transporting a

On 15 July 1945, a large wooden crate (5 ft high x 5 ft wide x 15 ft long) was loaded by crane onto Indy's main deck and was then transferred to the port hangar where armed marines were posted for guard duty around the clock.

Also, two metal canisters were hand carried from the dock up the ship's brow and then on to the Flag Secretary's quarters where they were chained to the deck with eye bolts. Two armed marines were then stationed at the quarter's entrance to begin guard duty (24/7).

A ten day trip to Tinian Island would begin on 16 July 1945 and Indy's arrival (to offload the cargo) was scheduled for 26 July 1945.

On 16 July, Indy departed Hunter's Point, CA .

Just 74.5 hours later, Indy arrived at Pearl Harbor for a brief stop to unload passengers and refuel.

The 2,091 mile voyage marked from Farallon Light, San Francisco (where Indy came out of

the channel after leaving Hunter's Point) to Diamond Head, Pearl Harbor, had set a new

US Navy Speed Record

After just a few hours in Pearl Harbor, Indy left port and was again underway for the

remainder of her trip to Tinian Island.

Indy arrived on schedule at Tinian Island on 26 July where the

was safely off-loaded.

was safely off-loaded.

The

was the components of "Little Boy" (the Atomic Bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima

to end World War II.

was the components of "Little Boy" (the Atomic Bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima

to end World War II.

Captain McVay's orders also included traversing the Philippine Sea from Guam to Leyte by following an almost directly westward route commonly referred to as

"Route Peddie."

McVay traveled without an escort which was unusual for a ship the size of Indy.

He was advised that there was a low probability that he would encounter enemy ships, so "Route Peddie" was recommended.

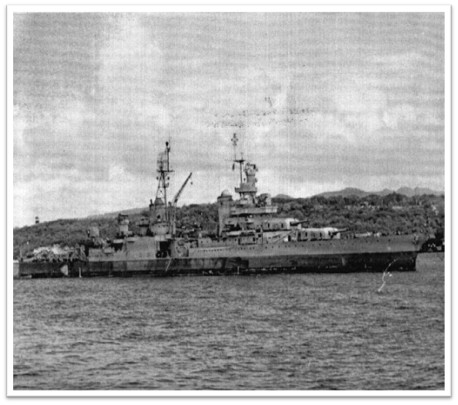

Here is an actual photo of Indy at Guam on 27 July 1945 (this photo is purported to be the

last actual photo of Indy)

Captain McVay's orders were to take Indy to Leyte to participate in training for his crew.

As previously mentioned, during the 2+ months of Indy's Mare Island overhaul, about 25% of his crew had turned over and were replaced by younger and very inexperienced sailors (many of whom had never been to sea).

Once training was completed, Indy would then be prepared to join other forces and participate in an imminent "Invasion of Japan."

Here is a depiction of Indy silhouetted in a very "peaceful" sunset

(a view that could have been seen before Indy's 28 July 1945 Guam departure)

Captain McVay had negotiated that Indy would travel "Route Peddie" at an SOA (Speed of Advance) of 15.7 knots per hour in order to complete an arrival at Leyte on the morning of Tuesday, 31 July.

He was advised to "Zig Zag" the ship "At his discretion."

Zigzagging was a defensive strategy in which the helmsman steered a ship back and forth at angles across the base course in order to throw off the calculations of enemy sub skippers attempting torpedo attacks.

Indy departed Guam at 0900 hrs on Saturday, 28 July 1945.

Many of the crew chose to sleep topside for a few hours (between their duty watches) during the darkness of the night of 28 July.

The evening air was sweltering hot (especially in confined sleeping compartments below deck), so Captain McVay invited the crew at their discretion to sleep out under the stars on the main deck.

The crew awoke on Sunday morning (29 July) in anticipation of enjoying a relaxing day onboard (church, meals, card games, etc.).

The only exception were the six 4 hour time periods throughout the 24 hour day when pre-assigned crew members would be fulfilling US Navy Duty Watch obligations (standard US Navy protocol).

During WW II (and throughout subsequent years following WWII), standard US Navy Operating Procedures for large ships required ¼ of the crew (at any point in time during a 24 hour period) to be officially assigned Duty Watch obligations for each established 4 hour shift.

In the minutes of time just prior to the end of a defined 4 hour shift period, a sailor (or marine) serving Duty Watch would hand over the watch responsibilities to a previously assigned and scheduled replacement.

A twenty-four day aboard US Navy Ships was divided into Six (6) Duty Watch Periods:

| 1 | Mid Watch | 0000 - 0400 hours | (12:00am to 04:00am) |

| 2 | Morning Watch | 0400 - 0800 hours | (04:00am to 08:00am) |

| 3 | Forenoon Watch | 0800 - 1200 hours | (08:00am to 12:00pm) |

| 4 | Afternoon Watch | 1200 - 1600 hours | (12:00pm to 04:00pm) |

| 5 | Dog Watch | 1600 - 2000 hours | (04:00pm to 08:00pm) |

| 6 | First Watch | 2000 - 2400 hours | (08:00pm to 12:00am) |

"The Bluejacket's Manual" is a sailor's "guidebook" which provides detailed information related to a sailor's daily life.

Critical information about the duties of a "War Lookout" (so called during times of war) were included in the

1943 Bluejacket's Manual 11th Edition

The last sentence in the Deck Seamanship Section of the manual states:

"Nothing should be taken for granted and

left unreported in a lookout's sector."

War Lookout Stations aboard a US Navy Ship were defined by dividing the 360 degrees of bearing arc into "Sectors" (usually 16).

Each Sector was 22 ½ degrees of arc width (22.5 x 16 = 360 degrees).

During WW II, there were Three (3) War Lookouts assigned to each Sector:

Water Lookout (for Submarines)

Horizon Lookout (for Ships)

Sky Lookout (for Planes)

A Water Lookout had the responsibility of visually searching his assigned ocean Sector to spot an enemy submarine on the surface!

This was especially important onboard Indy since the ship was NOT equipped with Sonar (used to detect submerged submarines) and her radar was also ineffective against submerged subs.

It was also important on Indy's voyage from Guam to Leyte as she was traveling alone and without having the protection of an accompanying ship (typically a Destroyer Escort).

Hundreds of crew members were again sleeping topside during the hot dark night hours of Duty Watch Period 6 on 29 July.

As the evening progressed, there was an overcast sky with pitch black visibility.

Because of poor visibility, Captain McVay directed that the ship stop zigzagging.

He instructed the OOD (Officer of the Deck) to recommence zigzagging should visibility improve.

Throughout the entire Duty Watch Period 6, all Indy personnel (and especially the assigned Water Lookout Watches) never actually saw any enemy naval craft on the evening of 29 July.

An Imperial Japanese Navy Submarine (I-58) was maneuvering near "Route Peddie" during

Indy's Duty Watch Period 6.

An Imperial Japanese Navy Submarine (I-58) was maneuvering near "Route Peddie" during

Indy's Duty Watch Period 6.

Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto was the Commanding Officer on I-58.

LCDR Hashimoto is depicted here at his sub's periscope.

Actual photo of Commander Hashimoto's IJN I-58 submarine

At 2226 hours (after the moon had risen), Hashimoto's sub was still submerged, but she rose to periscope depth. Hashimoto was under the impression that visibility was too poor to search for ships using the periscope.

At 2335 hours, I-58 briefly surfaced. Hashimoto was still looking through the night periscope when the I-58's navigator, using binoculars, shouted,

"Bearing red nine-zero degrees, a possible enemy ship."

Hashimoto then confirmed with his own binoculars and located Indy at a distance of 10,000 meters.

I-58 re-submerged and Hashimoto initiated his plan for an attack and acquired his target using his night periscope.

He directed his crew to prepare six Type 95 torpedoes.

He also ordered two

(suicide) pilots to stand ready as a possible

alternative weapon in the event the torpedo attack should fail.

(suicide) pilots to stand ready as a possible

alternative weapon in the event the torpedo attack should fail.

An extreme offensive weaponry used on Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) submarines was the use of a submerged torpedo that was "manned" by a suicide pilot.

Multiple Kaiten Suicide Craft were physically attached to the outer hull of a submarine and upon command could launch and the Kaiten's suicide pilot would steer the weapon to target to make a direct hit.

While Hashimoto was optimistic that he could successfully attack his target using Type 95 Torpedoes, he nevertheless gave the order,

"Kaitens Stand By."

At 2348 hours, I-58 was approximately 3,000 meters from Indy.

In the remaining minutes just prior to 2400 hours, Indy's watch personnel for Duty Watch Period 6 (for 29 July) were relieved and their replacements were on duty.

Watch personnel for Duty Watch Period 1 (for 30 July) then visually scanned the surface and saw nothing of concern since I-58 was submerged.

When I-58 was within 1,500 meters from Indy, Hashimoto ordered his crew to fire a spread of 6 torpedoes within the approximate time period of 2356 to 0002 hours.

At about 0002 hours, the first of two successful torpedoes hit the bow area forward of the 8" Gun Turret #I on Indy's starboard side.

Within seconds, the second successful torpedo hit close to amidships adjacent to the 8" Gun Turret #2 also on Indy's starboard side.

Additional multiple explosions from Indy's internal gasoline tanks and ammunition storage areas soon followed.

The first torpedo opened up most of Indy's bow and water began rushing in as the ship continued to move forward.

With the second torpedo explosion (and ensuing internal explosions), the ship began to list, first 2 degrees, then quickly on to 10, 25, 45 and finally 90 degrees onto her starboard (right) side.

All power was lost and internal communication systems were destroyed which prevented Captain McVay from receiving updates from engine rooms below.

Damage to Radio Rooms 1 and 2 impacted the ability to confirm whether distress signals were being transmitted or not.

By word of mouth, Captain McVay passed the message

"Abandon Ship."

USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was so severely damaged that it sank about 12 minutes after the second torpedo hit.

As a result of the rapid sinking, only a few life rafts were deployed and most men had only a kapok life Jacket or an inflatable life belt. There were many men who had no life supporting equipment.

About 200 ft of Indy's stern rose vertically out of the water as the ship descended and sunk bow first.

USS Indianapolis (CA-35) sank about midway between Guam and Leyte at approximately 0015 on 30 July 1945.

| Navy | Marine | Total | |

| Officers | 80 | 2 | 82 |

| Enlisted | 1,076 | 37 | 1,113 |

| Total | 1,156 | 39 | 1,195* |

* 1,194 Indy crew and 1 passenger (US Navy Captain Edwin Crouch)

| Onboard | Missing | Rescdued | Survived | |

| Officers | 82 | 67 | 15 | 15 |

| Enlisted | 1,113 | 808 | 305 | 301* |

| Total | 1,195 | 875 | 320 | 316 |

* Four (4) deceased post-rescue

An estimated 300 men went down with the ship.

About 100 men survived the sinking but had suffered severe and traumatic wounds sustained in the torpedo explosions. They would die within the first few hours after the sinking.

Another 475 men died in the water over the next 4 ½ days from multiple causes: dehydration, overexposure, exhaustion, intentional saltwater ingestion, hallucinatory driven attacks on fellow crew and frequent and multiple shark attacks.

Note that following rescue, dozens of bodies were identified and buried at sea by crew members serving aboard US Navy Recovery Ships,

In the Final Count, 879 men were recorded as

"Lost at Sea"

If you would like to learn the complete Story of

USS Indianapolis CA-35 (from 1932 to 1945),

Click Here